When he wasn’t misspending his youth, my husband Fred was building sets for Henry Lowenstein. There is so much to say about this Denver theater icon who was a dear friend to us and to so many others. Tony Garcia, who worked with Henry and now runs his own Denver theater, found room in his tribute when Henry died in 2014 to mention Festival Caravan, a free summer series Henry conceived and ran for the Bonfils, the grande dame of Denver performing arts venues.

"Festival Caravan gave thousands of people access to theater and ideas and art in communities where survival was a day to day activity,” Garcia said. “For communities in need of bread, Henry also brought roses. For young people of color, whose parents brought them out to see the theater, they were able to see surrogates of themselves on the stage sing and shine. Those shows offered a most valuable commodity — hope."

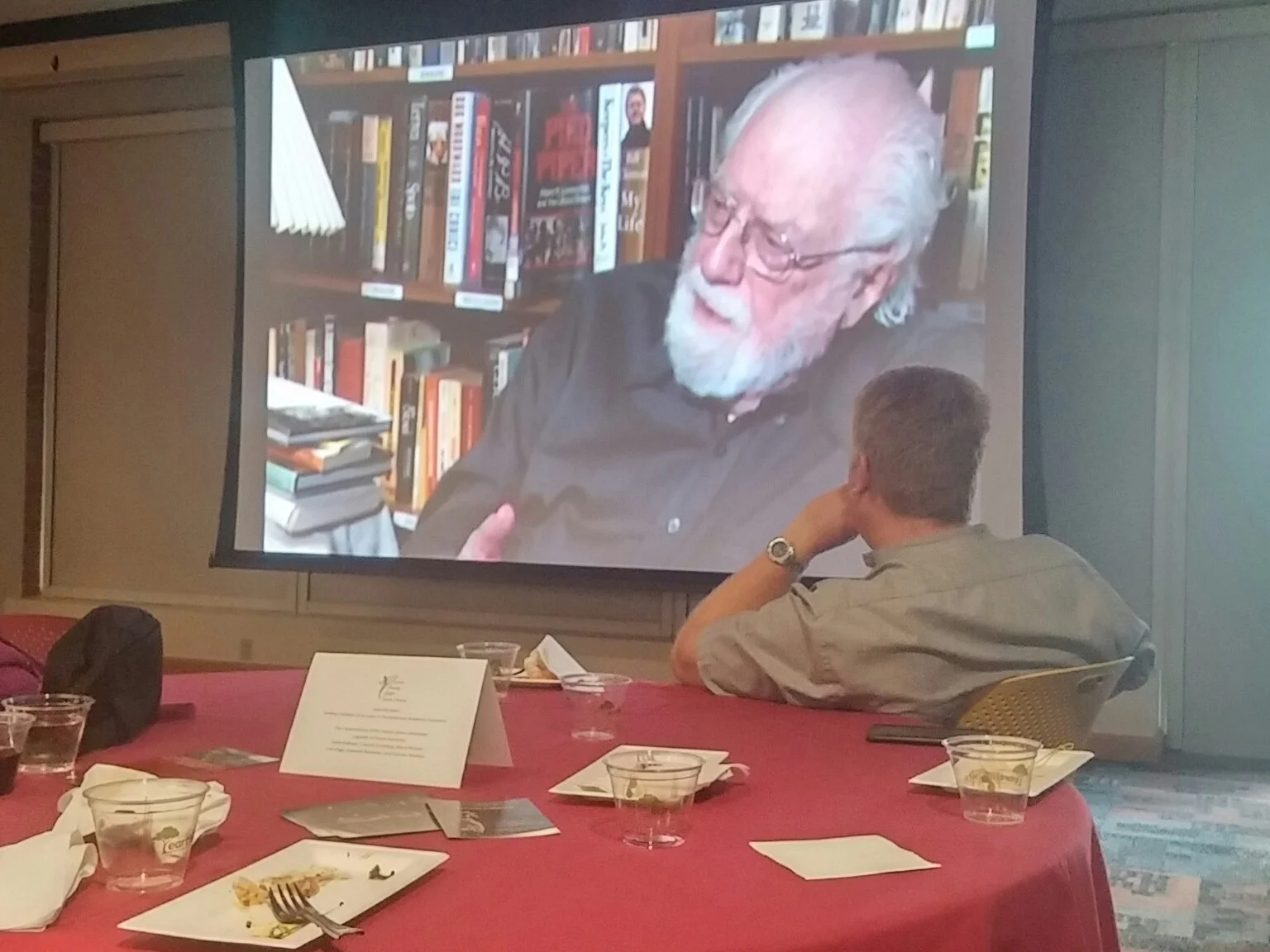

Today the Carson Brierly Giffin Dance Library at the University of Denver opened an exhibit and premiered a fluid and engaging documentary exploring Festival Caravan. Fred was interviewed for the documentary – and then they asked him to narrate it!

Performers, a Henry-designed mobile stage, lights, costumes and scenery were trucked to parks around Denver, drawing diverse audiences to equally diverse summer shows from 1973 until the summer before the Bonfils (by then renamed for Henry) closed in 1986. They put on Chicano protest plays, American Indian dance, klezmer, classical ballet and full-scale performances of shows like “Ain’t Misbehavin’” and “for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf.”

Henry commissioned a show tracing the state’s history for its centennial, which coincided with the nation’s bicentennial. He explained in an interview conducted some years ago for a Carson Brierly Giffin oral history project that he included a scene with hooded men and burning crosses to depict the political clout the Ku Klux Klan held in Colorado in the 1920s. Henry directed his actors to watch the audience carefully during the scene and be ready to defuse tension with this line:

“This is how it used to be. For heaven’s sake, let's make sure it never happens again.”

“I felt that theater, coming as a friend to different neighborhoods, could help bridge some of the differences,” Henry said in the oral history interview.

Carson Brierly Giffin archivist Nathalie Proulx sifted through Henry’s papers held at the Denver Public library for photographs, stage designs, notes and other memorabilia. Though she’s lived in Denver several years, she found some surprises in the Festival Caravan route.

“During my research, I was like, ‘Where the heck is THAT park?’’’ Proulx told me. She included Henry’s hand-drawn maps showing the city’s parks to underline what she called his “drive to bring art to all the different areas of Denver.”

Fred, a stage hand and driver for Festival Caravan during its last three years, went on to earn a BFA in theater design and production from the University of North Carolina School of the Arts. Fred still knows every park in Denver. And he can back a big truck into a tight spot.

Henry “really believed in human kind. And human kindness,” said Buddy Butler, who was an original member of New York’s Negro Ensemble Company and now teaches theater and directs in the San Francisco Bay Area.

The documentary Proulx produced featured Henry collaborators like Buddy and choreographer Cleo Parker Robinson, who received the 2017 Dance/USA Honor Award. Cleo said Festival Caravan was inspired by Joseph Papp’s Shakespeare productions in New York’s Central Park that began in the 1950s, and by a Depression-era federal program that brought performances to the masses on a mobile stage.

“Henry Lowenstein was just so open to that kind of community offering,” Cleo told me.

Henry, born in 1925 in Berlin, came to London as a refugee along with thousands of other young Jews in the months before World War II broke out. The experience shaped him profoundly, as was evident in a letter to the editor he wrote shortly before he died, when a wave of young immigrants to the United States was making headlines.

“I am an immigrant and a Holocaust survivor,” Henry wrote The Denver Post. “When I was 13 years old, England saved 10,000 Jewish children from certain death by allowing us to enter the country. We left families, most of whom we never saw again, and followed new life trajectories. Now, 75 years later, my heart goes out to the thousands of children fleeing from Central America to our country.

“This country did not show its compassion to my generation, many of whom could have been saved from the gas chambers. Will we turn our backs once again? Will politicians stop shouting about “illegals” and show some humanity?”

As Henry pointed out, the US and other Western countries closed their doors to many Jews fleeing Nazi persecution. Emblematic was the response in 1939 when more than 900 Jewish refugees sailed from Germany on the St. Louis. The St. Louis reached the coast of Florida after Cuban authorities cancelled the refugees' transit visas and denied entry to most of the passengers. The United States denied them permission to land and the St. Louis was forced to return to Europe. The governments of Great Britain, France, the Netherlands, and Belgium each agreed to accept some of the passengers. Of the 908 St. Louis passengers who returned to Europe, historians found 254 died in the Holocaust.

Henry reached the United States from Britain in the 1940s and studied theater design at Yale and worked as a stagehand on Broadway. He came to Denver first as a designer and then a manager for the Bonfils in the early 1950s. He made sure the Bonfils was a welcoming place. He hired Cleo’s late father Jonathan, who was black, over the racist objections of some. Jonathan Parker, known as JP, was initially hired as a janitor. He later became the first black actor on the Bonfils stage. JP would later work as a manager and professor at a Denver college’s fine arts center and as the first technical director of his daughter's company — Cleo Parker Robinson Dance.

These days the Denver arts community is discussing how to reach larger and more diverse audiences. In a cultural strategic plan called Imagine 2020, Denver leaders say it’s crucial "both for the health and survival of arts, culture and creativity in Denver and to better serve residents (that) approaches to increasing accessibility ... focus on meeting people where they currently are."

Cleo told me that people of all races and ethnic groups attended Festival Caravan performances in the hundreds and sometimes thousands.

“You wonder how you build those audiences again,” she said. “Maybe you have to go back to bringing art to the people.”

“You don’t just make a Festival Caravan,” she added. “That took us years and years to build and tweak. It takes some real expertise. We had top designers and people who were dedicated to theater.”

Cleo added that ideas and characters she developed for Festival Caravan are still part of her company’s repertoire. And she remains committed to bringing art to audiences.

Festival Caravan “hasn’t died for me,” she said.

It lives at the Carson Brierly Giffin Dance Library until March 23, 2018. You'll find the exhibit in a sunny reading room just outside the special collections area on the lower level of the university’s Anderson Academic Commons. You’ll also be able to watch the documentary. For more information call 303-871-4065 or check http://library.du.edu/collections-archives/specialcollections/dancelibrary.html

Library hours are Sundays 10 a.m.-2 a.m.; Monday-Thursday 7 a.m.-2 a.m.; Fridays 7 a.m.-10 p.m.; Saturdays 9 a.m.-10 p.m.

Yes, that’s 2 a.m. These are student hours. The library is open 24 hours during finals.